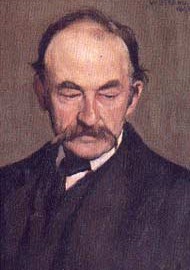

Story and Vision in the Poetry of Thomas Hardy

Laurence Coupe

E-Magazine 45 (September 2009), pp 35-38

Laurence Coupe discovers that the typical Hardy poem illuminates a moment set against a narrative framework. He argues that it is the tension between them that produces its special kind of beauty.

***

Conventionally poetry is divided into lyrics (short poems expressing an emotion or idea), narrative poems (telling a story) and dramatic poems (characters speaking as if in drama). But this rigid distinction doesn’t always apply. We might think in particular of the poetry of Thomas Hardy, a poet whose works often look like lyrics but have an underlying narrative or dramatic impetus that is often missed. In the ‘Preface’ which he wrote for his second volume of poetry, Poems of the Past and the Present (1901), Thomas Hardy declared: ‘Of the subject-matter of this volume – even that which is in other than narrative form – much is dramatic or impersonative even where not explicitly so.’

It is important to bear this in mind as one approaches Hardy’s poems: even if they do not announce themselves as stories, there is a lot more going on in them than the poet simply telling us how he feels or what he believes. The title of that volume gives us a clue: one of Hardy’s main concerns is the relation between ‘past’ and ‘present’. Given that we live in time, we inevitably make sense of our lives through narrative. This is something that he, more than nearly all other ‘lyric’ poets, fully understands.

Note also Hardy’s use of the word ‘impersonative’. Typically his own invention, he uses it to suggest a character, with his or her own story, as if in a play or novel. Before Hardy established himself as a poet he had already had a long and successful career as a writer of prose fiction. Indeed, many were written while he was still making his way in that genre. There is certainly something of the novelist’s skill evident in the poems, which seem deliberately to defeat our expectation of pure lyrical utterance. There is always some other sort of narrative ‘business’ going on, even when we assume that Hardy is simply expressing himself.

True, Hardy in his notebook once quoted approvingly his friend Leslie Stephen’s opinion that the aim of the poet should be ‘to touch our hearts by showing his own’. But ‘showing’ is a lot more subtle a process than ‘telling’, as any good novelist knows. It demands that the reader be drawn into the story, sympathise with the protagonists and enter into the world they inhabit.

Fools of time

No matter how closely a poetic utterance may seem to reflect whatever information we have about his life, we have to be careful not to simply equate speaker and author. It is no coincidence that a form of which Hardy was particularly fond was dramatic monologue. Here the ‘I’ is that of an impersonated character, who speaks in a specific setting and situation to another, silent character.

The classic instance of this form in Hardy’s work is the series of poems he wrote after the death of his first wife, Emma, and included in the section entitled ‘Poems of 1912-13’ in the volume Satires of Circumstance (1914). Of course, it would be foolish to deny that there is a connection between that event and that series of poems. However, it would be wrong to assume that each and every utterance is simply the expression of personal grief coming directly out of the experience of marital mourning. Hardy takes personal experience and crafts it into a more universal expression of bereavement.

We should not be misled here by Hardy’s use of the word ‘satire’ in the title just mentioned. If, in the conventional sense, it brings to mind poetry that exposes the folly of individuals and institutions, we should consider the effect of pairing it with the word ‘circumstance’. Shakespeare’s Sonnet 116 may declare ‘Love’s not time’s fool’, but what Hardy seeks to demonstrate is that most of us are indeed the fools of time, especially when falling in and out of love. ‘Circumstance’ – by which he means the uncontrollable conditions of mortal life – will always render us vulnerable and frequently ridiculous. But of course Hardy’s ‘satires’ are wholly his own, and are informed by his profound compassion.

In ‘The Going’, the persona begins by trying to justify himself for not realising, right up to the moment of death, that the deceased was fatally ill:

Why did you give no hint that night

That quickly after the morrow’s dawn,

And calmly, as if indifferent quite,

You would close your term here, up and be gone….

These lines expose his fallibility, but the ultimate point of the poem is to convey the depth of his regret, as is made clear in the desperation of the rapidly rhyming, shorter lines which succeed these:

Where I could not follow

With wing of swallow

To gain one glimpse of you ever anon!

Using a different verse form, but with similar effect, ‘The Voice’ conveys the abject state of mourning, the failure of the bereaved soul to find sanctuary from his pain: ‘Woman much missed, how you call to me, call to me…’ The abrupt generality of ‘woman’ compels our attention. The alliteration of ‘much missed’, intensifying the loss, is complemented by the repetition of ‘call to me’, whereby the echo of the words uttered only raises the cruelly taunting possibility that it is the beloved’s voice which is replying to him. ‘Can it be you that I hear?’ he desperately asks. Memories of happier days, when the ‘woman much missed’ would wait for him, wearing her distinctive ‘air-blue gown’, only add to the speaker’s torment. Such memories fuel his obsessive quest for the absent one, and we are left with a vivid presentation of his state of bewildered loss, enacted by the uncertain verse form:

Thus I; faltering forward,

Leaves around me falling

Wind oozing thin through the thorn from norward

And the woman calling.

‘Never again’

We may rightly categorise ‘The Going’ and ‘The Voice’ as dramatic monologues: there is a speaker (the bereaved one), and there is a silent listener, silent in this case because dead (the loved one). However, each poem implies a larger framework of narrative, a past state in which the man and woman were happy together, contrasted with a present state in which they are apart. Hence the desperate wanderings of the persona in ‘The Voice’ to locate a bodily presence which offers more than the mere echo of his own words.

In the case of ‘The Going’, the relationship between past and present, and so the overarching narrative, is rather more complex. For we have three, not two, moments in time to consider. The first is the distant past when the young man and the young woman were blissfully happy:

You were the swan-necked one who rode

Along the beetling Beeny Crest,

And, reining nigh me,

Would muse and eye me,

While life unrolled us at its very best.

The second is the recent past in which the mature man and woman became estranged:

Why, then, latterly did we not speak,

Did we not think of those days long dead,

And ere your vanishing strive to seek

That time’s renewal?

The third is the present, in which the persona is tormented by the contrast between the first and second moments:

Well, well! All’s past amend,

Unchangeable. It must go.

The sense of a narrative context is important for understanding another of the ‘Poems of 1912-13’: ‘At Castle Boterel’. Here, though, the temporal setting is slightly different. Firstly, we have the personal memory – that of the occasion when, in ‘dry March weather’, the persona and his beloved got down from the chaise they were being driven in, to ease the pony’s load, and simply enjoyed climbing the road together. Though this may seem a trivial enough incident, the persona begs to differ:

But was there never

A time of such quality, since or before,

In that hill’s story?

Secondly, we have the persona’s present lament: visiting Castle Boterel again, the persona imagines that he sees a ‘phantom figure’, that of the beloved, in the very same spot as she was when with him, all those years previously. He can only

… look back at it amid the rain

For the very last time; for my sand is sinking,

And I shall traverse old love’s domain

Never again.

However, both moments, that of memory and that of lament, are placed in the context of a larger temporal framework:

Primeval rocks form the road’s steep border,

And much have they faced there, first and last,

Of the transitory in Earth’s long order.

The particular story concerning the persona’s quest is seen against the background of the larger movement of events, which is subject to ‘Time’s unflinching rigour’. Human beings have to make what sense they can of their lives through telling their stories, while remaining aware that there is a larger story which contains theirs. They may defy it, as does the persona when he affirms that what the rocks ‘record in colour and cast / Is – that we two passed.’ But the closing phrase of the poem, ‘Never again’, gives the last word to ‘Time’.

‘Looking away’

Again and again, Hardy presents us with situations and stories in which characters find themselves subject to the cruelties of life in time. He shows us how we carry our stories around with us, and how they can dictate how we respond to the given moment. Much of our emotional energy is spent in our anguish about what has been and what might yet be. In ‘A Broken Appointment’, the persona is waiting for a woman who fails to meet him as promised, thereby showing she did not care for him. He describes himself as ‘a time-torn man’. In ‘The Self-Unseeing’ the adult speaker recalls a childhood occasion on which he danced to the sound of his father’s violin while his mother sat looking on:

Childlike, I danced in a dream;

Blessings emblazoned that day;

Everything glowed with a gleam;

Yet we were looking away!

Of the two poems just quoted, the first might be categorised, along with ‘The Going’, ‘The Voice’ and ‘At Castle Boterel’, as a dramatic monologue. The speaker addresses an absent personage, who may or may not be listening (most likely not, it seems). The second poem belongs to the broader category of the lyric. We use the term ‘lyric’ to refer to most short poems expressing a state of mind or feeling. While the poet may not adopt a role, as in dramatic monologue, it is still necessary to remind ourselves that the speaker is not necessarily the same as the poet: the ‘I’ may well be ‘impersonative’. Just as importantly, even though the lyric may offer itself as an isolated moment of reflection – on an event, on another person, or on a theme – there will inevitably be an implicit narrative.

‘Some blessed Hope’

Sometimes the parameters of time are suggested by the title itself. In ‘Afterwards’, the title suggests that the present will in due course become the past; what takes place now will be reflected upon ‘afterwards’. With the first stanza, what is implicit in the title becomes explicit:

When the Present has latched its postern behind my tremulous stay,

And the May month flaps its glad green leaves like wings,

Delicate-filmed as new-spun silk, will the neighbours say,

‘He was a man who used to notice such things’?

The persona is envisaging a future when he will not be here: the gate of the present moment will have been shut for ever; he will, in short, be dead. The question that occurs to him is this: when that has happened, will other people look out onto the sights of their world – the fragile beauty of Spring, in this instance – and remember him fondly as someone who, while he was alive, appreciated them – and, perhaps, taught others to do so? Or, to put this in another way again: in the future he will belong to the past; but will his name be invoked by way of a reminder to live in the present? He trusts that, though his question is here a rhetorical one, it will be answered positively in due course.

Narrative for Hardy is not always confined to individual lives. ‘The Darkling Thrush’, first published in The Times on 29th December 1900, and subsequently included in Poems of the Past and Present, takes history itself as its context, the bigger narrative in which people’s private narratives are positioned.

Though this is a lyric poem, it also has a narrative trajectory. The persona has been wandering amidst the bleak and gloomy setting of the countryside in winter, and now pauses to look about him:

I leant upon a coppice gate

When frost was spectre-gray.

He cannot help but project human qualities onto the scene and, simultaneously, the historical context:

The land’s sharp features seemed to be

The Century’s corpse outleant,

His crypt the cloudy canopy,

The wind his death-lament.

The direction of human history, as of individual life, is towards the ‘winter’ of death – the decline of civilisations, the encroachment of mortality. However, halfway though the poem Hardy brings in a contrary vision: the persona, who describes himself as ‘fervourless’, without passion or enthusiasm, becomes aware of ‘a full-hearted evensong / Of joy illimited.’ His melancholy sojourn has been rewarded, it seems. Out of the death of the year, the death of the century and the death of the persona’s spirit there arises, suddenly and miraculously, the promise of new life. This is all the more surprising since it emerges from the gloom by way of an ‘aged thrush, frail, gaunt, and small / In blast-beruffled plume’. This moment of vision cuts across the narrative of despair: though there seems to be ‘so little cause for carolings / Of such ecstatic sound’ that the persona cannot help but conjecture that the thrush’s song signified:

Some blessed Hope, whereof he knew

And I was unaware.

The religious quality of the language – ‘evensong’, ‘carolings’ and, of course ‘Hope’ (here capitalised, it is one of the Christian virtues) – cannot help but suggest the possibility of redemption. Hardy, an agnostic, leaves the implications of this language hanging in the air, along with the bird’s song; and the poem itself lingers in our minds. Is it possible that life is more than a story that ends in defeat? Hardy himself is silent; his persona is ‘unaware’.

But the point is that ‘The Darkling Thrush’, like so many of his other poems, continues to offer its readers a sense of the poignant beauty of the world, always accessible even where the narrative we inhabit seems remorselessly tragic. Insofar as we remain open to that beauty, and revere it, human life is justified and the poet’s work has not been in vain.

Laurence Coupe